Session 22 - Philemon

1 This letter is from Paul, a prisoner for preaching the Good News about Christ Jesus, and from our brother Timothy.

I am writing to Philemon, our beloved co-worker, 2 and to our sister Apphia, and to our fellow soldier Archippus, and to the church that meets in your house.

3 May God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ give you grace and peace.

4 I always thank my God when I pray for you, Philemon, 5 because I keep hearing about your faith in the Lord Jesus and your love for all of God's people. 6 And I am praying that you will put into action the generosity that comes from your faith as you understand and experience all the good things we have in Christ. 7 Your love has given me much joy and comfort, my brother, for your kindness has often refreshed the hearts of God's people.

8 That is why I am boldly asking a favour of you. I could demand it in the name of Christ because it is the right thing for you to do. 9 But because of our love, I prefer simply to ask you. Consider this as a request from me - Paul, an old man and now also a prisoner for the sake of Christ Jesus.

10 I appeal to you to show kindness to my child, Onesimus. I became his father in the faith while here in prison. 11 Onesimus hasn't been of much use to you in the past, but now he is very useful to both of us. 12 I am sending him back to you, and with him comes my own heart.

13 I wanted to keep him here with me while I am in these chains for preaching the Good News, and he would have helped me on your behalf. 14 But I didn't want to do anything without your consent. I wanted you to help because you were willing, not because you were forced. 15 It seems you lost Onesimus for a little while so that you could have him back forever. 16 He is no longer like a slave to you. He is more than a slave, for he is a beloved brother, especially to me. Now he will mean much more to you, both as a man and as a brother in the Lord.

17 So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. 18 If he has wronged you in any way or owes you anything, charge it to me. 19 I, PAUL, WRITE THIS WITH MY OWN HAND: I WILL REPAY IT. AND I WON'T MENTION THAT YOU OWE ME YOUR VERY SOUL!

20 Yes, my brother, please do me this favour for the Lord's sake. Give me this encouragement in Christ.

21 I am confident as I write this letter that you will do what I ask and even more! 22 One more thing - please prepare a guest room for me, for I am hoping that God will answer your prayers and let me return to you soon.

23 Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends you his greetings. 24 So do Mark, Aristarchus, Demas, and Luke, my co-workers.

25 May the grace of the Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit.

Author

Paul (with Timothy). Note that he is writing as a friend, not as an Apostle. Paul is in jail, "a prisoner for preaching the Good News about Christ Jesus".

Date of Composition

62-63AD.

Location, Purpose and Audience

Onesimus was a slave of Philemon, a businessman in the church at Colossae (Col 4:9). It appears from the text that he had run away with some of his master's property, and had gone to Rome, to lose himself.

There, he had encountered Paul (now an old man) and been converted (v. 10). They possibly knew one another, given that Paul knew Philemon. He had served Paul in prison for a short period; his presence and help had almost become indispensable to Paul; life in prison was particularly difficult in Roman times.

Onesimus legally belonged to Philemon and Paul decided that he must return home. Possibly Epaphras recognized him, from his own time in Colossae. Paul prepared a personal letter to Philemon, asking that Onesimus be received and forgiven, as a fellow-Christian.

By law Onesimus deserved severe punishment. Slaves were at the mercy of their owners, and runaway slaves were treated harshly. The danger of revolt was ever-present, especially in communities where slaves vastly outnumbered free people. Paul recognizes the huge risk involved in sending him back. Paul offers to repay whatever Onesimus owed (he points out that Philemon really owed him much more, in the Gospel). He expects that grace will win out and Onesimus will be restored into a superior relationship, as a brother in Christ.

The character of Philemon comes across in the letter. Paul describes him as a man of faith, loving, kind, generous toward others, charitable, an encourager. What a reputation.

There is no New Testament record of what eventually happened, but the preservation of the letter (and the fact that Philemon did not receive it alone, and file it out of sight) suggests that it circulated because it was a good news story and an equally good lesson. There is an a reference in a letter Ignatius (35-108AD, an early Christian martyr) wrote to the church at Ephesus when he was en route from Antioch to Rome to be executed:

"Onesimus, a man of inexpressible love, and your bishop in the flesh, whom I pray you by Jesus Christ to love, and that you would all seek to be like him. And blessed be He who has granted unto you, being worthy, to obtain such an excellent bishop." (Notice the same pun about being useful.)

There is no evidence that this was the same Onesimus, who would have been a young man when he met Paul; it is food for thought. The fact that the letter has survived is a good indication that Philemon received Onesimus back in the way Paul intended.

Literary Style and Structure

The letter is short, only 25 verses. Paul is tactful and courteous. This is a letter to a friend (and two others, who may be Philemon's wife and son; we cannot be sure), in whose house the church meets. But it is also written to the church at large.

Key Issues

Christian Love and Forgiveness

Forgiveness and reconciliation are prominent messages in this letter. Look at the steps:

- stating the offense - v. 11, 18

- showing compassion - v. 10

- interceding for the offender - v. 10, 18, 19

- substitution - v. 18, 19

- restoration to favour - 15

- elevation to a new relationship - v. 16

It is a "rubber hits the road" illustration of the Lord's Prayer: "Forgive our debts as we also have forgiven our debtors". Paul does not minimize the offense, but pleads for reconciliation, restoration and forgiveness.

"So if you consider me your partner, welcome him as you would welcome me. If he has wronged you in any way or owes you anything, charge it to me." (v. 17, 18)

Philemon evidently has a personal relationship with Paul. Possibly Paul won him to faith in Christ; or he was a blessing in his life for other reasons.

I, PAUL, WRITE THIS WITH MY OWN HAND: I WILL REPAY IT. AND I WON'T MENTION THAT YOU OWE ME YOUR VERY SOUL! Yes, my brother, please do me this favor for the Lord's sake. (V. 17-20).

God Makes Us Useful (regardless of our past)

There is a beautiful illustration (a pun, in the New Testament!) in v.11. The name Onesimus meant "profitable", but his past behaviour had been problematic. He had been unprofitable, but would now be useful on his return. Onesimus in name and Onesimus by nature. God makes us in His image, full of promise; we fail, but Christ makes us profitable again. Things obviously changed in the Onesimus related, to give Paul confidence in sending him back as a new man.

Paul does not demand that Philemon set Onesimus free; he does not call for slavery to end (some people have criticized him for this), but he asks that Onesimus be treated as a brother. This approach, repeated wherever people came to Christ, ended up undermining slavery. Christianity introduced new relationships across society (1 Cor 12:13; Gal 3:28, Col 3:11). Those changes made brothers out of slaves. The way they treated one another was now to be on the basis of their relationship with Christ; human classifications no longer had the same hold. Not that they could not take one another for granted, or take advantage of the changed relationship (see Eph 6:54-9 and Col 3:22-4:1), because everything had to be on the basis of God's love.

It is instructive that Paul's letter is written to the whole house church, as others would see Paul's unmistakable approach to forgiveness of Onesimus and this may affect their relationships with all of their slaves as well (assuming there were others). This would have had a snowball effect.

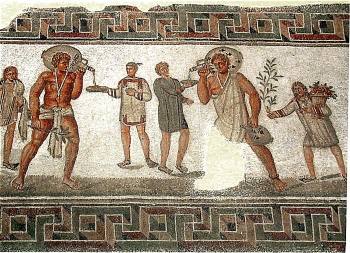

Slavery in New Testament Times

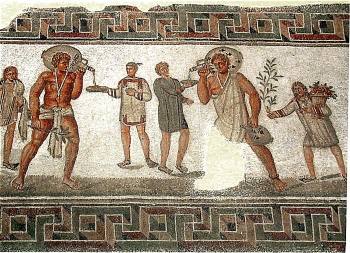

Slaves were very important to the Romans. Without slaves, the wealthy of Rome would not have been able to lead the lifestyles that they wanted to. Aristotle taught that it was in the nature of things that some people be slaves, to serve the higher classes.

Who were slaves? They were people who were frequently captured in battle and sent back to Rome to be sold. Abandoned children could be brought up as slaves. Roman law also stated that fathers could sell their older children if they were in need of money. A wealthy Roman would buy a slave in a market place. Young males with a trade could fetch quite a sum of money simply because they had a trade and their age meant that they could last for quite a number of years and, as such, represent value for money.

Once bought, a slave was a slave for life. A slave could only get their freedom if they were given it by their owner or if they bought their freedom.

If a slave married and had children, the children would automatically become slaves. There are cases in documentation from the period describing parents killing their children rather than allowing them to become slaves.

Slaves tend the hair of their mistress

No-one is sure how many slaves existed in the Roman Empire. Even after Rome had passed it days of greatness, it is thought by historians that 25% of all people in Rome were slaves; the proportions were much higher outside of Rome. A rich man might own as many as 500 slaves and an emperor usually had more than 20,000 at his disposal.

A logical assumption is that slaves led poor lives simply because they were slaves. In fact, a good master looked after a good slave as an equally good replacement might be hard to acquire - or expensive. A good cook was highly prized, as entertaining was very important to Rome's elite and rich families tried to outdo each other when banquets were held - hence the importance of owning a good cook. Other slaves might doctors, artists or tradesmen.

Slaves who worked down mines or had no trade/skill were almost certainly less well looked after as they were easier and cheaper to replace.

The Roman writer Seneca believed that masters should treat their slaves well, as a well-treated slave would work better for a good master rather than just doing enough begrudgingly for someone who treated them badly.

A large number of former enemy soldiers were used as slaves. This naturally led to slave rebellions. There were mainly three slave rebellions, The First Servile War (135-132 BC), The Second Servile War (104-100 BC) and the most famous (it was made into movies), the Third Servile war (73-71 BC) which was led by a Thracian gladiator named Spartacus.

Slavery was an important part of Roman society and culture. Romans, especially the rich ones depended greatly on their slaves for maintaining their lifestyles. Slaves were used for domestic help, manual labor, and gladiator fighting. Educated slaves were used as physicians, teachers and poets. Educated and skilled slaves carried a high price tag. Slaves made up a substantial part of the Roman population.

Christianity revitalized life in Greco-Roman cities by providing new norms and new kinds of social relationships. To cities filled with the homeless and the impoverished, Christianity offered charity as well as hope. To cities filled with newcomers and strangers, Christianity offered an immediate basis for attachment and acceptance. To cities filled with orphans and widows, Christianity provided a new and expanded sense of family, as widows and orphans would otherwise have been left to fend for themselves.

To cities torn by violent ethnic strife, Christianity offered a new basis for social solidarity. And to cities faced with epidemics, fires, and earthquakes, Christianity offered effective nursing and support services.

The capture of runaway slaves became an important aspect of the slave system in ancient Rome. For a slave to run away was considered legally a form of theft. A runaway female slave was considered to have stolen herself according to the law. Because the slave was considered the property of his or her master by running away a slave was stealing from the master. Running away then was something that (in Iegal terms) lay between the more minor offenses of petty theft and mismanagement, which resulted in beating, and the lethal attempt at sedition or plotting directly against the life of the master, a crime which would result in death. Running away then could not be considered a safe exercise by any means but it afforded some chance at liberty. However, if caught a slave could scarcely have hoped for mercy.

One early papyrus includes a letter from one Aurelius Sarapammon (who lived in Athens) to his agent, to go to Alexandria to search for a 35-year old runaway slave:

"You are to deliver him up, having the same powers as I should have myself, if I were present, to imprison him, whip him, and make an accusation before him against those who harboured him, with a demand for satisfaction."

For Reflection:

- Grace in our lives is often tested. How far would you be prepared to go if you were Philemon?

- Are there people in your life you feel are "not much use"; allow the Holy Spirit see what they could become with Christ genuinely in their lives.

- Paul led Onesimus to Christ in the depths of his prison experience; what a powerful lesson in how God can achieve long-term blessings in spite of our circumstances at the time.

- Are you prepared to welcome back and forgive people who have let you down, ripped you off, made mistakes that have cost you personally? It is easy to be indignant. It is easy to forget that we have also been forgiven much. Are you suspicious of their motives, afraid to be let down again? Can the love of God expand your thinking so that you give them a go and spend time encouraging them to greater heights in their lives?

- A key to becoming a person of generosity is to "understand and experience all the good things we have in Christ" (v. 6). Think about what God has given you, then allow your appreciation to flow into your relationships with others.